Part I: Statement in Poetry

Part II: External Evidence

Part IV: Public and Private Reading

Part V: Tenor and Vehicle

Part VI: Practice

Consider the following two lines of verse. The first is from John Dowland’s songbook and was written in the late 16th century. The second is from Wallace Stevens’ “Sunday Morning” and was written in the early 20th.

Fine knacks for ladies — cheap, choice, brave and new!

The world is like wide water, without sound.

In rhythm they could hardly be less alike. The first is choppy: it sounds like the spiel of a carnival barker. The second is as calm as the water it describes. However, they are metrically identical. They are both perfectly regular lines of iambic pentameter.

They sound so different because rhythm is not meter. Meter is the arithmetic norm, the background. It’s like a time signature in music. One of the odd things about poetry is that it is a simple, easily recognizable meter that makes possible complex rhythmic effects. Syllable length, strength of accent, placement of caesura all make individual lines of poetry move differently, yet no meaningful variation is possible without underlying regularity.

In scansion, whether a syllable is accented depends not merely on the amount of emphasis it receives but on its place in the line and the line’s place in the poem. In this famous line from Ben Jonson

Drink to me only with thine eyes

the last four syllables are accented progressively more heavily; yet in the context of the line, and the poem, which is iambic tetrameter, “with” is accented and “thine” unaccented. Long syllables are also often unaccented. In the above line the longest syllables in the line are the first and the seventh, and neither is accented.

The major difference between the lines from Stevens and Dowland is in the strength of the accents. Stevens’ line sounds calm and regular because all of the accented syllables are longer, and receive more emphasis, than all of the unaccented ones. In Dowland, neither is true, and the effect is radically different.

Nearly all pentameter lines have a caesura, or a natural pause, because most humans cannot speak ten syllables without drawing breath. In the Dowland line the caesura is at the dash, after “ladies”; it’s a long pause that absolutely cleaves the line. In the Stevens line there are actually two short caesuras, one after “world” and the other after “water.” Its continuity, its wateriness, is emphasized.

One can also vary the meter itself; not every iambic pentameter line must contain five perfect iambs. But most rhythmic variation is achieved by other means, and poets who complain that a rigid meter like iambic pentameter is too confining have probably not seriously investigated its possibilities. Even poets who employ traditional meters sometimes make the same mistake. When Michael Snider, who advocates traditional meters, says, “using traditional meters means I don’t have to teach my readers how to hear the rhythms of my poems,” he confuses meter with rhythm and gets the case exactly backwards. The simpler and more obvious the meter, the subtler the rhythmic effects that are possible against it — the more your readers have to learn.

Here are the caesuras in our Hardy poem, longer pauses marked with a double slash:

My spirit / will not haunt the mound

Above my breast, //

But travel, // memory-possessed,/

To where my tremulous being found

Life largest, // best.

My phantom-footed shape will go, //

When nightfall grays, /

Hither and thither / along the ways

I and another / used to know

In / backward days.

And there you’ll find me, / if a jot

You still should care

For me, / and for my curious air; //

If otherwise, then I shall not, //

For you, // be there.

Each stanza ends with a four-syllable line, with a caesura in each: first after the third syllable, next after the first, and last in the middle, resolving the other two the way a note resolves a chord.

The metrical scheme is perfectly iambic, with three exceptions, all worth noting. Each of the poet’s two self-descriptions, “tremulous being” at line 4 and “curious air” at line 13, contains an extra unaccented syllable, which ties them together. The back-and-forth of “hither and thither” is beautifully conveyed by the inversion of the first foot in the line. It’s easy to overanalyze this sort of thing, but Hardy is one of the finest metrists in English, and I am certain that he heard these effects, even if he didn’t stoop to analyze how he produced them.

All of these effects can be traced back to meter, the one thing that distinguishes poetry from prose. Even free verse has meter, which is to say it’s not really “free” at all. The scansion of free verse is a large subject that I will save for another day, but here’s a heuristic: the one thing that free verse cannot be is iambic, because that’s what ordinary speech is. Loosely iambic free verse inevitably tightens up into blank verse, or devolves into prose. Almost all bad free verse contains large undigested chunks of iambs, like lumps in the mashed potatoes. If you find them, you’re not reading poetry. You’re reading prose broken up at odd places on the page.

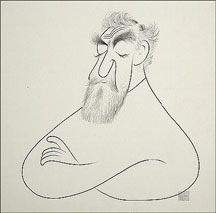

He died just shy of 100, the greatest and best-known caricaturist of the 20th century, and he drew until the very end. It is odd to say he was underrated, but familiarity bred, if not contempt, then more familiarity and when you saw him every week in the Sunday

He died just shy of 100, the greatest and best-known caricaturist of the 20th century, and he drew until the very end. It is odd to say he was underrated, but familiarity bred, if not contempt, then more familiarity and when you saw him every week in the Sunday